Ghosts

© Erik Tomasson

Ghosts

The title of Christopher Wheeldon’s Ghosts—that single, potent word—evokes vivid images. The name for the ballet, the choreographer’s sixth commission for San Francisco Ballet, comes from its score, composed by C.F. Kip Winger. Without that title the music could have been interpreted in many ways, but once you hear the word “ghosts,” there’s no turning back. Lovely, serene passages face repeated attacks by forceful, chilling interludes, as if something out there doesn’t want to be forgotten.

Winger, a bassist for Alice Cooper in the 1980s, formed his own eponymous band in the ’90s, releasing two platinum albums, Winger and In the Heart of the Young. He met Wheeldon in 1997, when a friend, Zippora Karz, took him to watch rehearsals at New York City Ballet. Ten years later, inspired after seeing three of Wheeldon’s ballets, Winger decided to write a piece for him. At the time, the composer was working in a recording studio that had been a hospital in the early 1900s, and he “could sense a mystical presence in the atmosphere,” he says. “The title Ghosts popped into my head when I was writing the cello solo in the first movement.”

Wheeldon describes the score as “kind of silvery, the way the piano creeps in and out.” Wondering if it might have a narrative, he read Henrik Ibsen’s Ghosts “in case [the play and the music] happened to align, and of course they don’t,” he says. “And then I thought maybe it’s just the atmosphere of ghosts. Maybe [the dancers] are ghosts but they’re not telling a specific story.” In his early explorations of theme, the choreographer turned to the poems of Edgar Allen Poe: “The City in the Sea,” “To One in Paradise,” “Lenore,” and “The Valley of Unrest.” With evocative phrases like “death looks gigantically down” and “lilies . . . that weep above a nameless grave,” the poems influenced Wheeldon’s creative process without becoming literal onstage. He ended up wanting to create the atmosphere of a mass gathering of souls, such as might occur after a tragedy. “It’s more like perfume than a heavy sort of ghost story,” he says.

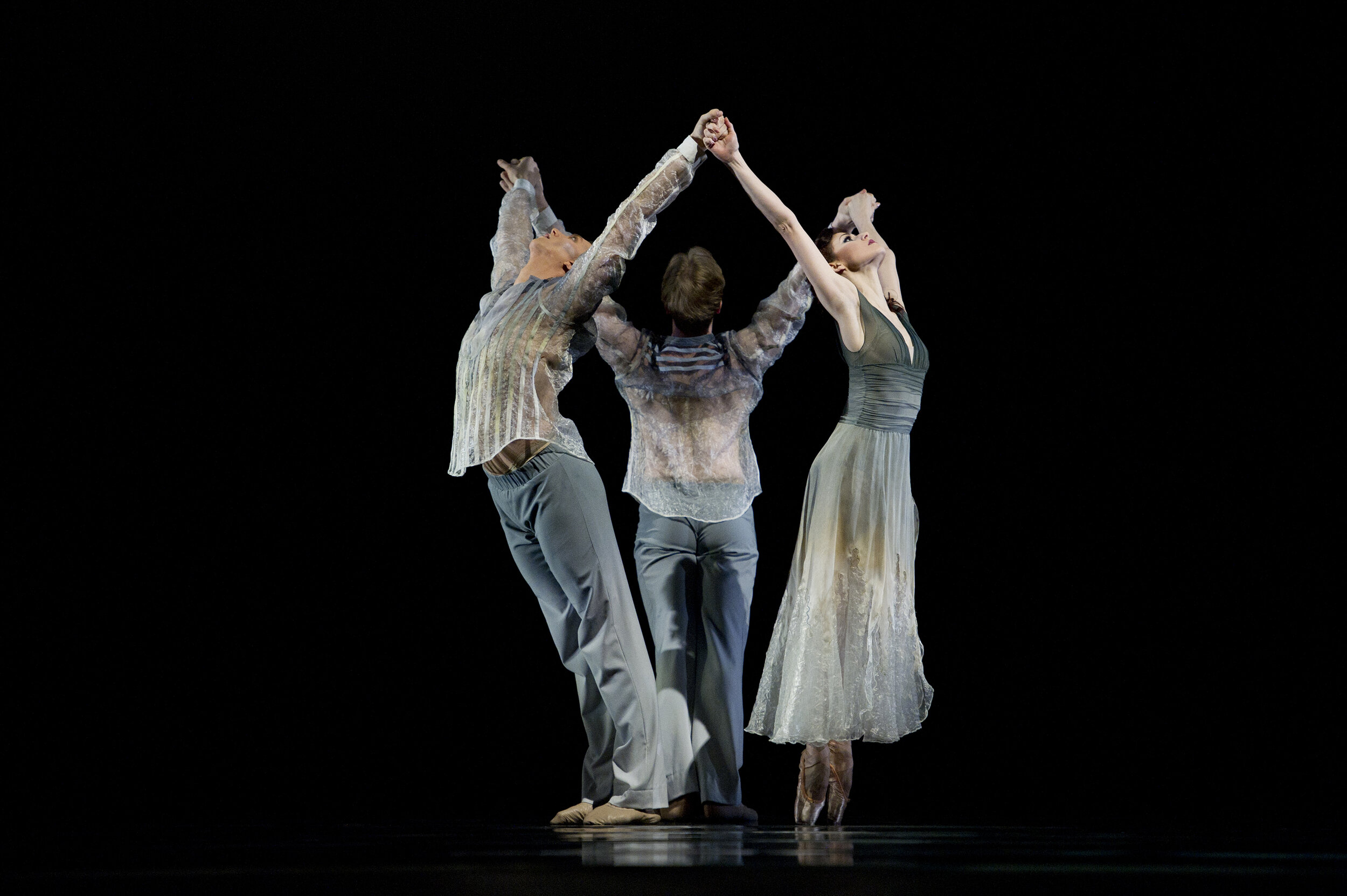

According to Principal Dancer Yuan Yuan Tan, who dances the pas de deux, Wheeldon didn’t suggest images of ghosts and death to her during rehearsals. She approaches the role as if “it’s a relationship, like husband and wife. That’s how it feels—just like moments of tenderness,” she says. “It’s extremely difficult. [Principal Dancer Damian Smith and I] do a lot of intense movement, but it’s so beautiful.”

For Smith, what makes the partnering difficult is that “every moment there is an intertwined, off-balance partnership that never seems to unwind, a kind of thread that’s constantly knotted.” And though the music might be legato, he says, the dancing should be “very sharp, direct, and precise, to kind of go against the music, and then choose moments when we are more lyrical and soft with the arms.” Wheeldon wanted to emphasize the shifts in contrast, Smith says. “He wants a definite transition between those two qualities of movement—strong and sharp and direct, and then soft and seamless.”

In terms of movement, Wheeldon says he loves “the freedom of not ever putting any restrictions on what I do in the studio.” Twists on classical steps expand the ballet’s vocabulary: chaînés (two-footed turns) speed up into spins; slow, leaden walks push across the floor; women on pointe drag one leg behind them (“an homage to Michael Jackson,” Wheeldon says).

As he has matured as a choreographer, Wheeldon has found that the rewards of his art have changed. What goes before audiences is still very important to him, he says, but earlier in his career he “wasn’t fully absorbing the riches of the process itself. And now that’s my favorite thing. Now it’s about all the discovery—the first time you see the model, the first time you run the pas de deux, the first time you see the set onstage—those are all really magical moments.”

by Cheryl A. Ossola

Creative Team

Choreography

Christopher Wheeldon

Composer

C.F. Kip Winger

Scenic Design

Laura Jellinek

Costume Design

Mark Zappone

Lighting Design

Mary Louise Geiger

World Premiere: February 9, 2010—San Francisco Ballet, War Memorial Opera House; San Francisco, California